-

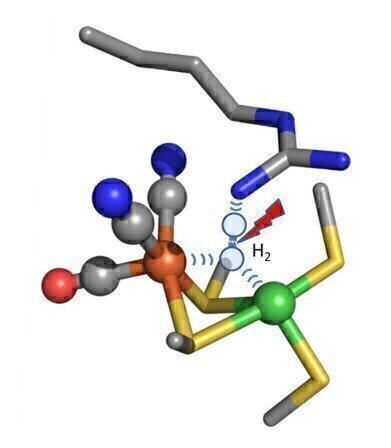

Hydrogen split flash “Hydrogen gas, which has two hydrogen atoms joined together (H2) is trapped between iron and nickel atoms (orange and red) and other parts of the enzyme. It is pulled apart to generate two separate hydrogen atoms and a flow of electricity”

Hydrogen split flash “Hydrogen gas, which has two hydrogen atoms joined together (H2) is trapped between iron and nickel atoms (orange and red) and other parts of the enzyme. It is pulled apart to generate two separate hydrogen atoms and a flow of electricity” -

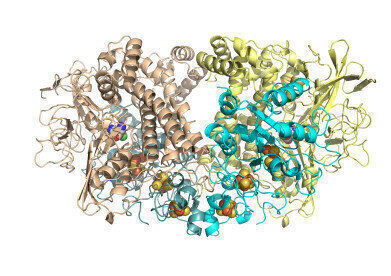

Hyd1 overall cartoon with cofactors Hydrogenase is made of four chains of protein folded up and holding atoms of nickel and iron buried inside to form a site where hydrogen gas can be split

Hyd1 overall cartoon with cofactors Hydrogenase is made of four chains of protein folded up and holding atoms of nickel and iron buried inside to form a site where hydrogen gas can be split

News & views

Bacteria’s Hydrogen Splitting Secrets Revealed

Jan 20 2016

Researchers have worked out how some bacteria rip hydrogen apart to produce energy, just like a biological fuel cell.* In the process they question the current ideas of how this happens and possibly move one step closer to a cheaper, more efficient, hydrogen economy.

The scientists used a combination of different techniques to work out what happens at the heart of bacterial enzymes called nickel iron hydrogenase. One of the authors Professor Simon Phillips, Director of the Research Complex at Harwell in Oxfordshire said: “The hydrogenases can do two things with hydrogen gas, turn it into protons and electrons or recombine them to form hydrogen. This can be done in a fuel cell but with platinum. Evolution has produced bacteria that can do it with nickel and iron, cheap and plentiful metals.”

While determining how the hydrogenase works, the researchers studied altered enzymes that were less efficient using Diamond Light Source’s x-ray Crystallography facility to work out and compare the structures of the original and changed enzyme. Professor Phillips said: “We got very accurate structures of the mutant and basically nothing moved apart from the atoms of the amino acids. So the loss of activity is not down to a change in structure or the loss of the metals. Diamond was crucial in determining this. “

This confirmed that reduction in activity had to be due to chemical, not physical changes and the scientists discovered that the splitting activity was caused by tension occurring between the atoms of nickel and iron. Hydrogen trapped in this area of tension splits apart creating energy. Keen to see if they can watch it in action. They are hoping that Diamond’s vacuum chamber for x-ray crystallography will be able to detect the very weak signal given by the hydrogen inside the enzyme. Simon Phillips said: “This unique facility means that we might improve the signal to noise ratio by a factor of ten which could let us see the hydrogen in place.”

The research was conducted by a collaboration between researchers from the Universities of Oxford and Dundee, and the Harwell campus in Oxfordshire.

*Published in Nature Chemical Biology

Digital Edition

Lab Asia 31.6 Dec 2024

December 2024

Chromatography Articles - Sustainable chromatography: Embracing software for greener methods Mass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles - Solving industry challenges for phosphorus containi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 22 2025 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 22 2025 Birmingham, UK

Jan 25 2025 San Diego, CA, USA

Jan 27 2025 Dubai, UAE

Jan 29 2025 Tokyo, Japan